City Cemetery

(est. 1869)

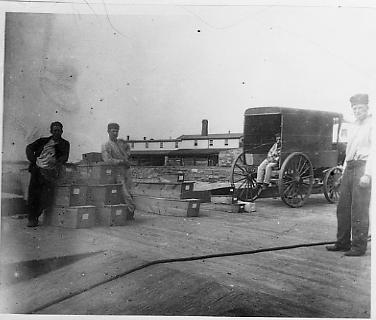

The first municipal burial on Hart Island took place on April 20, 1869, for a 24 year old housekeeper named Louisa Van Slyke who was born at sea and died of tuberculosis at the Charity Hospital on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island). Ten days following her death on April 10, Louisa’s coffin was loaded onto a steamer docked at the city morgue at Bellevue Hospital on East 26th street in Manhattan. The hold of the boat carried prisoners from the Blackwell’s Penitentiary Workhouse. The steamer journeyed eighteen miles up East River through the Hell’s Gate and into the Long Island Sound where a team of convicts laid Louisa in her grave on Hart Island.

By 1882, two hundred young men convicted of misdemeanors and sentenced for up to a year were living on the northern end of Hart Island called “the Hill” in barracks built during the Civil War. Their sentences required them to work burying the dead and maintaining the landscape. In the 20th Century, the Hart Island Branch Workhouse expanded ten-fold and moved to and a newly constructed prison dormitory at the south end of Hart Island, known as “the Hollow” A Branch Charity Hospital for “incurables” with infectious diseases such as tuberculosis that killed Louisa van Slyke also opened in the Hollow.

Eventually all the healthcare institutions closed while the cemetery remains active. When the Hart Island Workhouse closed in 1966, inmates were transferred to Rikers Island. They returned to living on Hart Island briefly in 1981-85. Up until the onset of COVID in 2020, they continued to travel by bus and ferry to bury the dead. Contracted labor now performs city burials on Hart Island.

The burial process on Hart Island is unique to New York City and culturally significant. It is linked to methods for handling the dead invented during the American Civil War. Thomas Brennan, Commissioner of the Department of Charities and Correction and Warden at Bellevue Hospital, set up the first municipal morgue in North America and adopted a Civil War practice of photographing bodies not identified by a medical examiner.

At first the “unknowns” were buried in individual graves and the “unclaimed” in large trenches. Most city burials are unclaimed which simply means that a private funeral director was not retained to collect a body from the morgue. The enormity of these common graves made disinterment difficult. A grid system developed during the Civil War to inter Union Soldiers on battle fields so that they could be removed to National Cemeteries was adopted in 1872. Bodies were laid out in three layers of fifty per layer with 150 per plot. In 1931, the layout changed to rows, two across and three deep with 50 per section and three sections. Each plot of 150 adults or 1000 infants is numbered and marked, now using GPS, but previously with wood or cast concrete markers. Once a body is fully decomposed to skeletal remains, the city has a right to reuse the grave.

Because older burial plots can be reused, New York City has a sustainable system with no shortage of space. City Cemetery on Hart Island is the largest municipal cemetery and largest natural burial ground in the United States. People are reluctant to choose Hart Island as an affordable green burial due to lingering stigma of city burials. However, the end of employment of prisoners to bury the dead and the removal of buildings creates an opportunity to reconsider Hart Island’s role as part of New York City’s green infrastructure and climate change solutions.